The Learning Tree, 1969

Directed by Gordon Parks

35 mm color film

107 minutes

Warner Bros./Winger

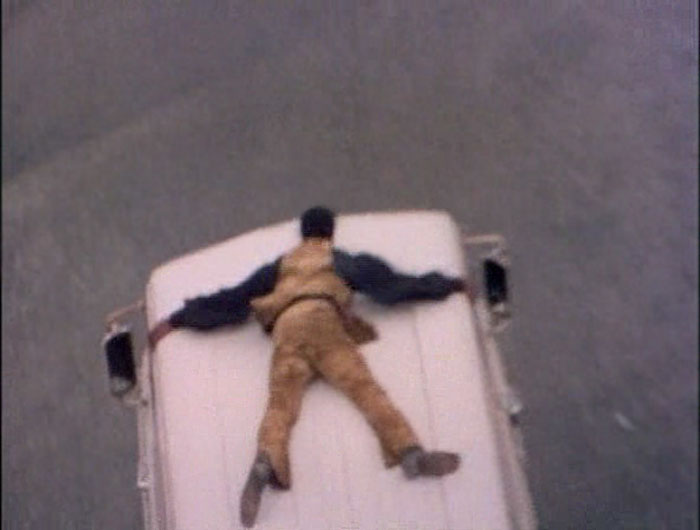

Shaft, 1971

Directed by Gordon Parks

35 mm color film

100 minutes

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song, 1971

Directed by Melvin Van Peebles

35 mm color film

97 minutes

Yeah

In the early 1970s, a new generation of black filmmakers challenged the stereotypical or compromised black characters then customary in Hollywood pictures. With calls for diversity growing, and a larger black middle class demanding to see itself represented, social, political, and economic pressures inside and outside the commercial film industry helped create opportunities for black directors. As early as 1969, Warner Bros. financed the production of Gordon Parks’s drama The Learning Tree, a semiautobiographical, humanistic recounting of black life in Depression-era America. The film established Parks as the first black director of a major Hollywood studio film. His Oscar-winning hit Shaft, about a suave private investigator in Harlem (Richard Roundtree), introduced into mainstream cinema the African American action hero; until then, action-hero roles had been reserved for white actors.

With the commercially viable Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song, whose protagonist triumphs over corrupt Los Angeles policemen bent on framing him for a murder he did not commit, Melvin Van Peebles expanded the limits of black male representation. This independent film, which no studio would produce, portrayed the almost unthinkable in mainstream popular culture: a tough African American hero who stands up to white power and authority and wins. Van Peebles saw his film as a political intervention, an antidote to decades of emasculated or docile characters. “For the Black man, Sweetback is a new kind of hero,” the director commented shortly after the film’s premiere. “For the White man, my picture is a new kind of foreign film.”

Still, despite the profitability of a handful of movies such as Shaft and Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song—often labeled “Blaxploitation” films by critics, both in and out of the black community, because of their violent content and lurid story lines—the commercial movie industry was hardly an accessible or important place for black cultural expression. Supporting projects with large budgets, and inevitably dependent on box-office revenues, the studios were generally risk-averse, and therefore unwilling to fund movies that could not attract a large national audience. Throughout the modern civil rights era, few race-related projects were green-lighted, and relatively few African American performers appeared in Hollywood productions.

Maurice Berger