I couldn’t bear the thought of people being horrified by the sight of my son. But on the other hand, I felt the alternative was even worse. After all, we had averted our eyes for far too long, turning away from the ugly reality facing us as a nation.

Let the world see what I’ve seen.-Mamie Till Bradley

In September 1955, shortly after fourteen-year-old Emmett Till, who was visiting family on summer break, was murdered by white supremacists in Money, Mississippi, his grieving mother, Mamie Till Bradley, distributed to newspapers and magazines a gruesome black-and-white photograph of his mutilated corpse. Although the mainstream media rejected the photograph as inappropriate for publication, Bradley was able to turn to African American periodicals for assistance.

Asked why she would do this, Bradley explained that by seeing, with their own eyes, the brutality of segregation, Americans would be more likely to support the cause of civil rights. “The whole nation had to bear witness to this,” she insisted.

Bradley’s brave gesture represents one of the most decisive moments in the civil rights movement. The publication of the photograph in Jet and other black periodicals helped transform the modern movement, inspiring a new generation of African American activists to join the cause. It also affirmed the capacity of visual images to jolt Americans, black and white, out of their state of denial or complacency.

Image Credits/Captions (Click on thumbnails for full image)

Photographer unknown. Bo at Thirteen, Christmas 1954

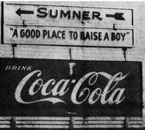

Page from Ernest C. Withers. Complete Photo Story of Till Murder Case, 1956. Offset lithography on paper. ©Ernest C. Withers Estate, courtesy Panopticon Gallery, Boston, MA. This twenty-page photo booklet was self-published and sold for a dollar by Ernest Withers, one of a handful of African-American photojournalists to cover the trial of Tills’ killers. Withers’ compelling images challenge the eye to focus on details in order to reap their subtle, ironic observations—an effect epitomized by a seemingly mundane black-and-white shot of a large Coca-Cola sign. The image is transformed by a single, penetrating detail: a plaque affixed to the sign with the motto of the town where Till’s murderers were tried and acquitted—“Sumner, A Good Place to Raise a Boy.”

Emmett Till in Casket, 1955. Courtesy Chicago Defender. Charles Diggs, the first black congressman from Michigan, declared the photograph “the greatest media product in the last 40 or 50 years, because [it] stimulated a lot of interest and anger on the part of blacks all over the country.” Activist Joyce Ladner recalls that it motivated young African-American protesters, the soldiers of the “Emmett Till Generation” as she calls them: “All of us remembered the photograph of Emmett Till’s face . . . [It] galvanized a generation as a symbol—that was our symbol—that if they did it to him, they could do it to us.”